Engineering Predicament – Fuel for Engineers

Engineering mindset

It is natural in engineering to tackle problems, either given as assignments or found during a common workflow. It is natural for an engineer also to seek problems to solve, even from places where there shouldn’t be any.

Engineering professionals are often faced with a problem or a predicament requiring thorough planning, designing, verification and implementation. Those steps can be accompanied by a techno-economic study, calculations on the total cost of ownership (TCO) and a schedule for return on investment (ROI). Sounds familiar? Sounds like some of the phases and building blocks of a somewhat typical engineering predicament. The predicament, not in a negative way, but in a challenging sense that something needs to be solved fundamentally by means of engineering.

For a motivated manager of the predicament, the challenge is welcomed and awaited, often desired. It is embedded in the executor’s mindset to gather information on similar anterior challenges and how they were tackled in order to avoid reinventing a solution, which has already been invented. For an engineer, it is imperative to apply efficient working methods throughout a project.

The predicament and its solution

Engineering 101: if there is a problem, there is a solution (not necessarily chemical). The problem, however, is often self-made, an offspring of another already solved predicament. Pure problems, fundamental predicaments, are the ones that the executors are after. They come from new requirements that are often followed by the familiar phases, but also offer the opportunity to develop and deploy something extraordinary or at least to come up with something entirely new. These predicaments can be the fuel for engineers and motivate them to perform maintaining high standards. Needless to say, in new technology projects, an engineer able to master multi-disciplinary functions is a valuable asset.

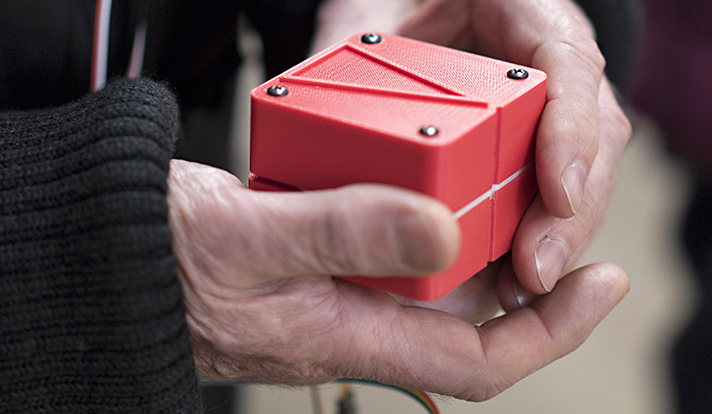

As for the solution, there may be many, of which some are executable and some not. Sometimes it can solve the original predicament, but generate others. That can be, however, the expected result. If something can be solved without revising the design, it most likely will not be a success. This also is embedded in the executor’s mindset. A solution often requires verification, testing, and validation. To come up with a test plan for a new design can be even intimidating because you don’t necessarily realize everything that should be tested. Design validation forms one of the most important phases of an engineering process. During validation, the learning curve of the design’s features truly begins and can be extremely fruitful in tackling expected problems in future revisions.

By taking on a predicament of engineering, you will guide yourself to produce a solution, preferably an executable one. It can take you from frequent disappointments to moments of careful joy and back to the depths of conundrums and uncertainties. If the design is promoted to the state of ‘In Production’, the measure of the executor’s feeling of success can be highly affected by the arduousness of the process. The lowest of lows can produce the highest of highs. Induction transforms to conduction.